Comenzar, comenzar de nuevo

1

Una luz rasa e intensa atraviesa la alta ventana,

zapatos nuevos resuenan en el parqué pulido,

una ráfaga de polvo de tiza flota en el aire.

La mente llena de verano todavía,

de correr, jugar hurling, espacio.

Otro curso por delante.

La cabeza de un argivo en el libro sin estrenar,

con casco, barba y un templo detrás,

un trirreme abajo en la bahía.

Tinta nueva, papel intacto, el mundo

se abre silenciosamente en el sur.

Donde emigran las golondrinas.

Trescientos hombres y tres hombres.

Esparta. Las islas de Grecia.

Odiseo zarandeado por las olas. Alejandro.

Barcos y vino tinto, sol bajo los pinos,

uva y olivas amargas, ásperos muros luminosos.

Infancia del mundo.

Torre circular en el cuaderno; redacciones antiguas

sobre tormentas invernales, sangre y saqueo.

Vuelvo la espalda al viento del norte,

no me interesan los vikingos ni morir por oro.

El sur se ha apoderado de mi corazón.

Ese invierno supe que éramos pobres,

al subir Fair Hill en la lluvia sesgada

con zapatos agujereados para jugar al hurling en el barro y el frío;

me imaginé envejeciendo allí, en un mundo escaso

y me negué. El sueño de otro lugar prendió en mí.

2

Después, años de la vida que llamamos real.

La cuestión irlandesa, la larga marcha

por el trabajo y el amor,

el asesinato condimenta el viento amargo, nuestras agotadoras

y sinceras discusiones, lento raciocinio;

intentando hacer el bien con pequeños gestos; años

de profundizar donde se vive y ¿qué

es mi país? Tedio y alegría a partes iguales,

la edad acrecentada y la rabia a fuego lento;

trabajo y evasión, trabajo y evasión,

la tensión entre lo que te reclama y lo que eliges.

La gran libertad aparente de nuestro oficio:

lo inventamos todo. Las palabras me eligen

y las acepto, erguido y terco:

Sunión, Shandon, Hermes, Atenas, hogar.

Las redes de las que huimos y hallamos; lo que nos encuentra.

El hogar está donde se ensancha el corazón,

y ella tiene mi corazón, al que apenas esperaba conocer,

sus pasos se acomodan a los míos con dulce avenencia

donde los botes aproan en el muelle

y el cordero ensartado humea por la noche

mientras desciframos el alfabeto, familiar y desconocido,

el calor del día suaviza los huesos al anochecer.

3

Soñaba con las empinadas callejuelas de Ereo

cuando subía las de mi ciudad natal.

Los barcos al atardecer en las calles de El Pireo

eran los barcos cargados de noche en el muelle Penrose.

En el promontorio de arcilla de Fountainstown los pinos

se elevaban con la profunda soledad de los de Therma,

soy todavía ese niño, en dos sitios a la vez

que restriega el pie y sobrevuela los tejados.

Me tumbo bajo la luna del cazador,

el aire preñado de polen, la isla un murmullo,

para comentar el día desde que nos hemos despertado

en el frescor de la mañana, el día perfumado de resina.

Desayuno en el cafeneion, miel y yogur,

tus ojos tan fríos como el Egeo al fondo, tu mano

que busca la mía cuando nos sentamos de costado al mar.

Anoche soñé que estábamos en Kato Zakros,

paseando por las ruinas de los palacios a la luz de la luna,

los taxis impacientes en la última taberna, los camareros

hablaban de Dublín con alguien quemado por el sol.

El pescado en Shandon relucía sobre el borde iluminado del cerro,

hurlers chocando hombros y gritando en la playa pedregosa.

El cartero nos ha despertado, has puesto un dedo en mis labios

y has sonreído: «kali mera1 —has dicho—, kali mera, mi amor».

4

Vamos y venimos.

Vivir no es tan sencillo como cruzar el mar.

La voz de la que huyes a veces te encuentra.

Al regresar de Agios Kyricos, ¿cuándo?, ¿hace dos días?

Sacudido por las olas y sereno con una canción en la mente.

Torann na dtonn le sleasaibh na long

ag tarraingt go teann’n ár gcann fé sheol2.

El aula de nuevo, una amplia perspectiva se abre hacia atrás

las colinas de West Cork, esa costa profundamente dentada

y barcos en el mar, que llegan desde el sur y el oeste,

desde el este: el influjo azul de la historia, el reflujo del comercio.

Al arriar velas esta mañana en las calles frente a El Pireo,

en mi interior un anciano adujaba los cabos.

La amiga de Therma pasea con nosotros por el ágora,

hay algo de mi madre en ella,

lo sopesa todo, atrapada en el remolino de la conversación,

ojos brillantes y vivaces, su mano el pico de un ave

raudo para palpar la fruta o sacar monedas del bolso.

Y algo de mi padre en Stephanos, cuando nada

en Agriolykos, ojos azules apacibles, fuerte a los ochenta.

Sintonizaste la melodía en mis pensamientos, murmuraste

Measaim gur súbhach don Mhumhain an fhuaim3…

tus dedos se aferraron a los míos; lo vi claro:

Mi país no es lo mismo que mi lugar.

Entre un momento y el siguiente, una bocanada de dicha.

Acomodamos el paso, pasamos de la luz a la sombra

y a la luz otra vez, en el bochorno del tráfico,

en el vaivén de la conversación por donde paseó Platón.

Un día cualquiera en la Atenas de Munster, suaves vocales del Ática,

aula de polis y templo, cuna del pensamiento.

La ciudad blanca de la infancia es la misma en todas partes.

Esta vida profundamente dentada es la misma en todas partes.

Begin, Begin Again

1

Flat hard light through the high window,

new shoes rapping on the polished parquet,

a drift of chalkdust hung on air.

My head still full of summer,

running and hurling, space.

A fresh year laid out before us.

Head of an argive in the new book,

helmeted, bearded, a temple above him,

a trireme below in the bay.

Fresh ink, fresh paper, the world

quietly opening to the south.

Where the swallows go.

Three hundred men and three men.

Sparta. The Isles of Greece.

Wave-tossed Odysseus. Alexander.

Ships and dark wine, sunlight under the pines,

grapes and sour olives, rough bright walls.

The childhood of the world.

Round tower on the copybook; last year’s tales

of winter storms, of blood and plunder.

I turned my back to the north wind,

no interest in Vikings, in death for gold.

The South took all my heart.

That winter I learned we were poor,

climbing Fair Hill in the slanting rain

with leaking shoes, to hurl in the mud and cold;

I saw myself growing old there in a small world

and I refused. Some dream of otherwhere took hold.

2

And then, years of the life we must call real.

The Matter of Ireland, the long march

through work and love,

murder salting the bitter wind, our weary

earnest arguments, slow thought,

trying in small ways to do good; years

of dig where you stand and what

is my nation? Tedium and joy in equal measure,

the increments of age and rage slow burning;

work and escape, work and escape,

the pull between what claims you and what you choose.

The great, slant freedom of our craft:

we make it all up. The words choose me

and I accept them, straightbacked & stubborn:

Sounion. Shandon. Hermes. Athene. Home.

The nets we flee, and find; and what finds us.

Home is where the heart grows.

I have my home where my heart is, and she

has all my heart whom I scarcely hoped to know,

her foot falls with mine in sweet accord

where the small boats nose at the quay

and lamb smokes on the spit at evening

as we puzzle the alphabet, familiar and strange,

the heat of the day softening our bones in the dusk.

3

The stepped lanes of Eressos are the lanes I dreamed

walking the stepped lanes of my native city.

The ships at twilight in the roads at Piraeus

are ships that sat heavy with night on Penrose Quay.

The pines at Fountainstown on the clay bluff

stand in the same deep solitude over Therma,

I am that boy still, in two places at once,

rapping his foot and soaring over rooftops.

I would lie down under the Hunter’s moon,

the air heavy with pollen, the island a murmur,

and talk the day back to where we woke

in the cool of morning, the day fresh with resin.

Breakfast in the cafeneion, honey and yoghurt,

your eyes cool as the Aegean beneath, your hand

searching mine as we sit sideways to the sea.

Last night I dreamed us back in Kato Zakros,

walking the ruined palace in moonlight,

taxis revving at the last taverna, the waiters

chattering of Dublin to somebody sunburned.

The fish on Shandon glittered over the rimlit ridge,

there were hurlers shouldering and calling on the stone beach.

The postman woke us, you reached to brush my lips

and smiled: Kali mera, you said. Kali mera my one love.

4

We come and go.

To live your life is not so simple as to cross the sea.

The voice you turn from will sometimes find you out.

Making out from Aghios Kirikos, what, two days ago?

Wave-tossed and sober, an old song in my head.

Torann na dtonn le sleasaibh na long

ag tarraingt go teann ‘n ár gceann fé sheol.

That schoolroom again, a long perspective opening back—

hills of West Cork, that deep indented coastline

and ships on the sea, from the south and west,

from the east; the blue inrush of history, outrush of trade.

Dousing sail this morning in the roads off Piraeus,

somebody old moving through me, coiling the lines.

Our friend from Therma walks with us in the agora,

something of my mother about her,

sizing it all up, caught in the whirl of talk,

her eyes glinting and shrewd, her hand a bird’s beak

darting to palp fresh fruit, pluck coins from out her purse.

And something of my father in Stephanos at Agriolykos,

swimming out into the bay, still blue-eyed, hale at eighty.

You locked onto the tune in my head, murmured

Measaim gur súbhach don Mhumhain an ceol…

your fingers tightened in mine; something came clear:

What is my nation is not the same thing as what is my place.

Between one moment and the next, a breath of grace.

We found our stride, stepping from light into shade

and out into light again, buffeted by the traffic,

held in the sway of talk where Plato walked.

An ordinary day in Athens of Munster, soft-vowelled Attica,

schoolroom of polis and temple, birthplace of thought.

The white city of childhood that is everywhere the same. This one life that is everywhere the deep-indented same.

Regreso a La Canea

He vuelto a La Canea de nuevo

pero, de repente, cargado de años.

Las chicas de bronce pasan en parejas,

casi a través de mí.

¿Soy un fantasma en el aire nocturno?

Esta mañana he despertado en El Pireo para tomar el barco,

y al vestirme he pensado en el otro ferri

que tomaré dentro de poco. Sorprendido,

me he parado entre sorbo y sorbo de café.

Huesos viejos, querido corazón palpitante,

cuántas mujeres han apoyado riéndose

la cabeza en ese pulso,

algunas polvo ya, otras

un misterio, madres, abuelas.

No ha sido lo que esperábamos.

Me falta aliento para describirlo; las vidas

que tuvimos, ágiles como las de las chicas de bronce

o los jóvenes veloces que abarrotan la plaza,

eternidad en toda respiración y mirada.

Creía que mi vida era un catálogo de pérdidas,

ahora, sin querer, la veo como ganancias;

Arrebatado por la esperanza, aturdido, tanta risa

y amor, tanta alegría regresada.

Return to Hania

Here I am come to Hania again

but now, suddenly, full of years.

The bronze girls go by in pairs,

almost they walk through me.

Am I a ghost in this evening air?

This morning I woke in Piraeus to catch the boat,

and thought as I dressed of that other ferry

I must take before long. Amazed, I hung

between one mouthful of coffee and the next.

Old bones, dear beating heart,

how many laughing women

once laid their faces to that pulse—

some are already gone to dust, others

are mysteries now, mothers, grandmothers!

It has not been what we expected.

It beggars breath to speak of it; such lives

we have led, who were lithe as the bronze girls

or the quick young men who throng the square,

eternity in their every breath and glance.

I thought my life a catalogue of loss—

now, without meaning to, I see it all as gain;

I am dizzy with hope, stunned—so much laughter

and love, such joy come round again!

El mito de Platón

En el mito de Platón nos encontramos en una caverna amplia,

numerosos y murmurantes en la oscuridad.

Por la entrada, en solemne procesión

pasan hombres y mujeres portando estatuas; un perro ladra

a lo lejos, las cigarras conversan, la luz es intensa pero agradable

conforme las sucesivas imágenes se graban en la mente.

El mito, muthos, el aliento de la realidad

el mundo, concebido idealmente, respira y después canta.

Luz en todas partes, luz afuera,

el mundo se presenta como un recuerdo.

Es el orden soñado por un autócrata,

los poetas desterrados, el gobierno del mejor.

Mi mente reflexiona, da vueltas y pregunta:

¿Qué estatuas son? ¿Quién las ha fabricado?

¿En qué orden se transportan?

¿Quién adoctrinó a los porteadores? Y,

¿qué hemos de aprender?

Yo lo veo así: nos revolvemos en la oscuridad,

nos alzamos y damos vueltas, la conversación comienza.

Una mujer avanza hasta la boca de la cueva,

se estira, sale a la luz primigenia.

Plato’s Myth

In Plato’s myth we are seated in a great cave,

numerous and murmurous there in the dark.

Across the cave mouth in a grave procession

pass men and women bearing statues; a dog barks

far off, cicadas chatter, the light is hard but kind

as each successive image prints on mind.

Myth, muthos, the breath of the real—

the world, ideally conceived, breathes and then sings.

Light is elsewhere, light is outside,

the world appears as the memory of things.

This is an autocrat’s dream of order,

the poets banished, rule by the best.

My mind ponders, stirs itself to ask:

What statues? Made and shaped by whom?

And carried in what order?

Who briefed the crew to carry them? And,

what is the story we are to understand?

I prefer this: we stir there in the dark,

we rise and walk about, the talk starts up.

Somebody makes her way to the mouth of the cave,

stretches, steps out into first light.

Kato Zakros

La llaman la garganta de la Muerte.

En lo alto, las cuevas sepulcrales

horadadas en la roca amarilla.

Arena en el suelo y polvo, todo límpido, preciso.

Tus sandalias tropiezan aquí, allí y más allá

claridad hipnótica de piedra y asfódelo,

idéntico al azul del pañuelo que te sujeta el pelo.

Llevas un bastón combado como un arco,

y tu aura centellea, despides luz.

Marcas el paso constante del cazador, listo para ir

donde sea, para arriesgarlo todo instintivamente,

y yo necesito agua, necesito ánimo, necesito descansar.

Sigo la bandera azul y tu pelo,

tu cabeza un pájaro luminoso que atraviesa la garganta

que se detiene una, otra, incontables veces.

Fragmentos de vasijas, parte de la boca, un trozo de asa

me agacho para recogerlos, el sol entre los altos muros

y mi cabeza tensa por el calor.

Agito mis talismanes confiando en que te vuelvas,

ensucio la huella del alfarero con la mía.

Qué diáfano todo, ni un soplo de viento

hasta que me golpeas los pulmones con la mirada.

Los corazones dan un vuelco, lo sé, lo siento, todavía lo siento

aquí en la oscuridad, siguiéndote a través de la luz del sol.

Kato Zakros

It is called the Gorge of The Dead.

The burial caves are punched in yellow rock,

spiked by a jeweled fist, an invader’s.

Sand underfoot, and dust, everything clear, precise.

Your sandalled foot falls there, and there, and there—

mesmeric clarity of rock and asphodel,

the exact blue of the scarf that binds your hair.

You carry a bent stick as if it were a bow,

and flare at the edges, light coming out of you.

You have the hunter’s steady lope, ready to go

anywhere, risk anything on instinct,

and I need water, I need courage, I need rest.

I follow the blue flag and your hair,

your head a bright bird darting the Gorge

stooping now, and now, and now.

Potsherds, a fragment of rim, a handle-stump—

I bend to pick them up, sun high between walls

and my head hard in the heat.

I rattle my talismans, hoping to make you turn,

greasing the potter’s thumbprint with my own.

How clear it all is, not a puff of air

until you punch my lungs with a look.

Hearts leap, I know, I felt it, I still feel it

here in the dark, tracking you through sunlight.

de GRIEGO

Dedalus Press. Dublín. 2010

Traducción del inglés de Enrique Alda

NOTAS

- «Buenos días» en griego. ↩︎

- El retumbar de las olas en los costados del barco que se acerca a toda vela. ↩︎

- Creo que la noticia será bien recibida en Munster. ↩︎

Para leer los poemas de Theo Dorgan en PDF, haga click en el siguiente enlace:

Para escuchar los poemas de Theo Dorgan, haga click en el siguiente archivo de audio:

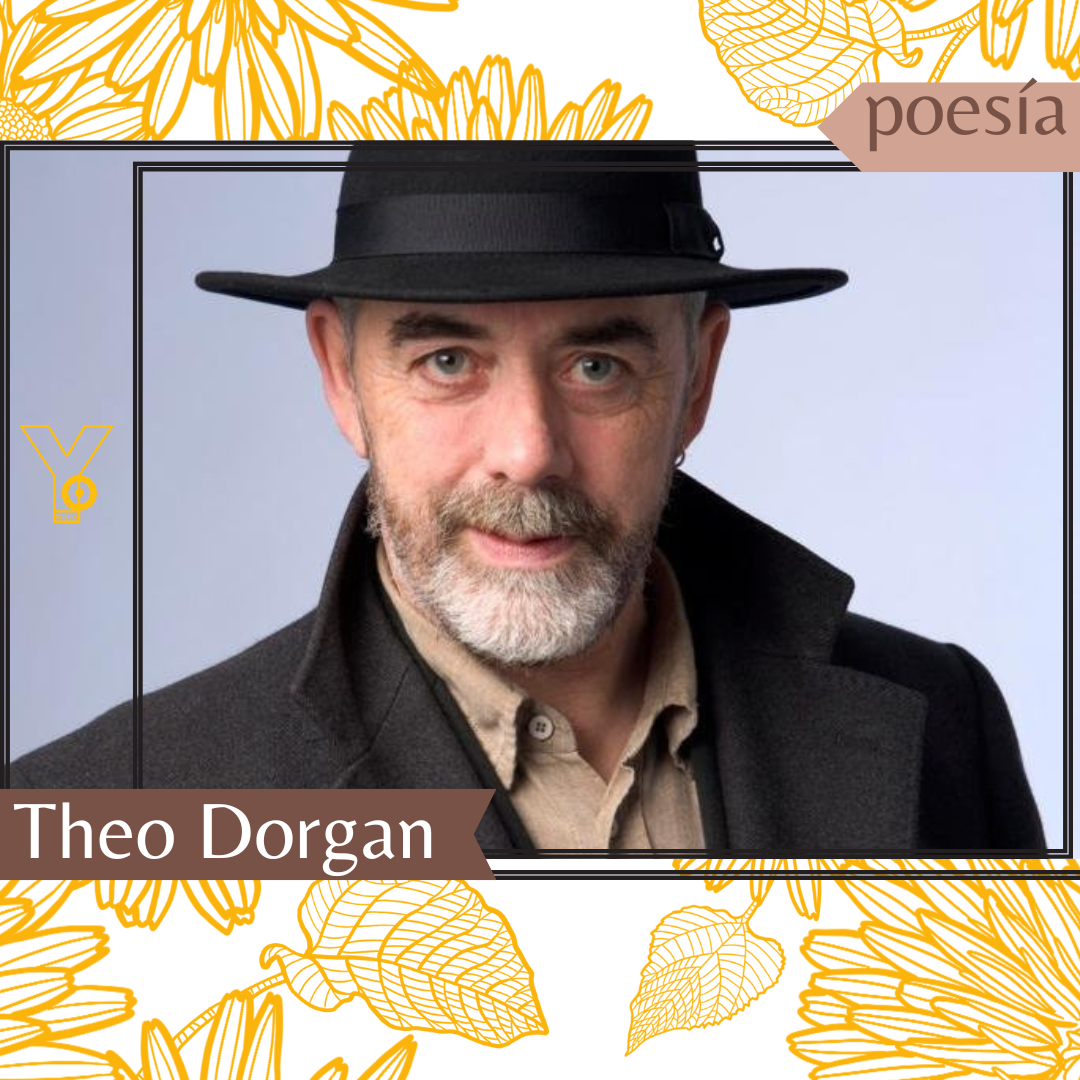

Theo Dorgan [Cork, 1953] es poeta, novelista, editor, ensayista, guionista y traductor irlandés. Es licenciado en Inglés y Filosofía por la University College Cork y tiene además una Maestría en Arte en la misma casa de estudios. Entre sus libros de poemas destacan The Ordinary House of Love (1990); Sappho’s Daughter (1998); GREEK (2010); Orpheus (2018). Sus poemas han sido traducidos al francés, español, italiano, rumano, ruso, griego, japonés, esloveno, alemán y portugués. Su novela Making Way fue publicada en 2013. Es miembro de Aosdána.

Enrique Alda es licenciado en Traducción e Interpretación por la Universidad de Salamanca y lleva veintisiete años dedicado exclusivamente a la traducción. Ha vertido al castellano más de ciento cincuenta libros. En los últimos tres lustros ha centrado sus esfuerzos en la literatura y poesía irlandesa, y reparte su tiempo entre las montañas de Wicklow y las estribaciones del Moncayo.